Empirical Exercise 4 in Python

In this exercise, we’re going to replicate the difference-in-differences analysis from

Does a ban on informal health providers save lives? Evidence from Malawi

by Professor Susan Godlonton and Dr. Edward Okeke. The authors estimate the impact of Malawi’s 2007 ban

on traditional birth attendants (TBAs) on a range of birth outcomes. At the end of the exercise, we’ll export our

regression results to excel using openpyxl, as we did in Empirical Exercise 3.

This exercise is also available as a colab.

Getting Started

The data set E4-GodlontonOkeke-data.dta contains information (from the

2010 Malawi Demographic and Health Survey)

on 19,680 live births between July 2005 and September 2010. Each observation represents a birth. Create

a python program that opens the Stata data set in python (using pd.read_stata from pandas and including the option

convert_categoricals = False). You should have received the data set over email, and

you will need to save it and load it to python from your computer. Your code for starting the script should look something like:

# ECON 523: EMPIRICAL EXERCISE 4 IN-CLASS ACTIVITY

# A. Student

# preliminaries --------------------------------------------

## libraries

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

from openpyxl import load_workbook

from openpyxl.styles import Alignment, Font, Border, Side

## file path

mypath = f"C:/Users/me/ECON-523/E4-DD2/"

# load data ------------------------------------------------

e4data = pd.read_stata(pjpath + "E4-GodlontonOkeke-data.dta",

convert_categoricals = False)

Make sure to import numpy, pandas, and statsmodels.formula.api, as always.

In-Class Activity

Question 1

To implement difference-in-differences, we need to add the following columns/variables to the e4data data frame:

- a dummy variable for the post-treatment period,

- a dummy variable for the treatment group, and

- an interaction between the two

The post variable is already present in the data set, one of the columns of e4data. What is the mean of post? What fraction of the observations in the data set occur in the post-treatment period?

Hint: remember that you can find the mean of the column varname in data frame df with df.varname.mean().

Question 2

The time variable indexes the month and year in which a birth took place. In the original data set, it is in Stata’s date format, and it reads into python in datetime64[ns] format. The same information is also contained in the variables birthyr and birthmonth. Cross-tabulate time and post or birthyr and post to see how Professor Godlonton and Dr. Okeke define the post-treatment time period in their analysis. What is the first treated month?

Hint: you can use pd.crosstab() to cross-tabulate two variables.

Question 3

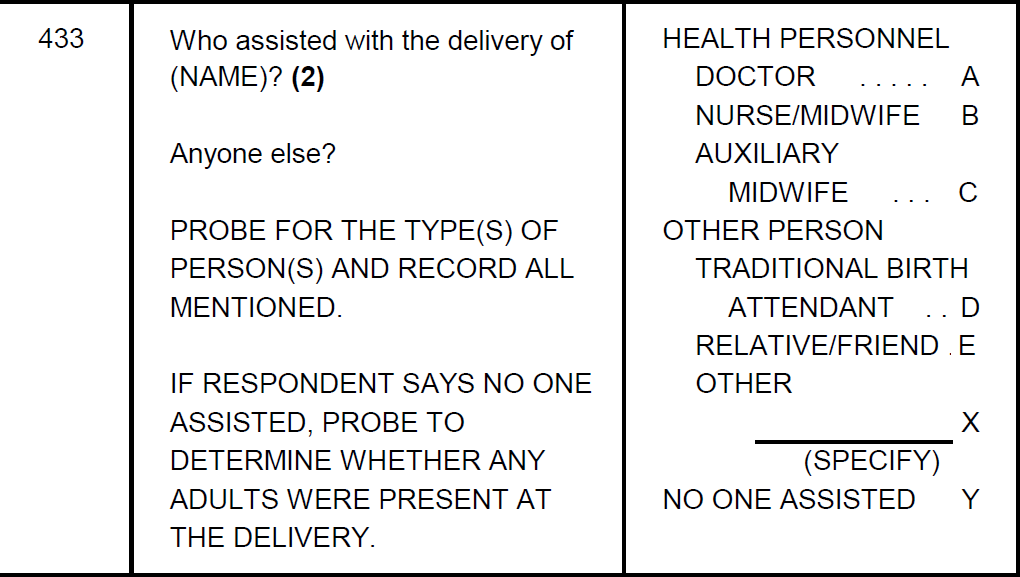

We need to define an indicator for the treatment group. Professor Godlonton and Dr. Okeke define the treatment group as DHS clusters (i.e. communities) that were at or above the 75th percentile in terms of use of TBAs prior to the ban. Data on use of TBAs comes from responses to the question below:

Responses have been converted into a set of different variables representing the different

types of attendants who might have been present at the birth. Tabulate

the m3g variable, which indicates whether a woman indicated that a TBA was present at a birth. What pattern of responses do you observe?

Hint: Use df.varname.value_counts() to tabulate a variable. A value of 0 indicates no, 1 indicates yes, and 9 indicates don’t know or a refusal to answer.

Question 4

We want to generate a dummy variable that is equal to one if a TBA was present at a particular birth, equal to zero if a TBA was not present, and equal to missing if a woman did not answer the question about TBAs.

There are several different ways to do this. The code below illustrates a simple approach using np.where().

e4data['tba'] = np.where(e4data['m3g'] == 9, np.nan, e4data['m3g'])

This generates a new variable, tba, that is the same as the m3g variable except that tba is equal to missing for all

observations where m3g is equal to 9. (It is usually better to generate a new variable/column

instead of modifying the raw data, because you don’t want to make mistakes that you cannot undo.) You can confirm that the new variable

looks as expected using either value_counts() or pd.crosstab() with the dropna = False option.

Question 5

We want to generate a treatment group dummy - an indicator for DHS clusters where use of TBAs was at or above the 75th percentile prior to the ban. How should we do it?

The variable dhsclust is an ID number for each DHS cluster. How many clusters are there in the data set?

Hint: use df.varname.nunique().

We can use group_by(dhsclust) before generating the conditional mean in the pre-treatment period, as the code below illustrates:

e4data['meantba'] = e4data.groupby('dhsclust')['tba'].transform(lambda x: x[e4data['post'] == 0].mean(skipna=True))

Question 6

The code below illustrates how to define a scalar cutoff equal to the 75th percentile

of the variable meantba.

cutoff = np.percentile(e4data['meantba'], 75)

Add this to your code and then create a new column/variable (in the e4data data frame) called high_exp that is an indicator

for DHS clusters where the level of TBA use prior to the ban exceeded the cutoff we just calculated. Replace this variable with NA

for observations where data on the use of TBAs is missing (i.e. when m3g equals 9). What is the mean of high_exp?

Question 7

The last variable we need to conduct difference-in-differences analysis is an interaction between

our treatment variable, high_exp, and the post variable. Generate such a variable as a column

in the e4data data frame. I suggest calling it highxpost.

Question 8

Now you are ready to run a regression. Regress the tba dummy on high_exp, post, and

highxpost. What is the difference-in-differences estimate of the treatment effect

of the TBA ban on use of informal birth attendants? How do your results compare

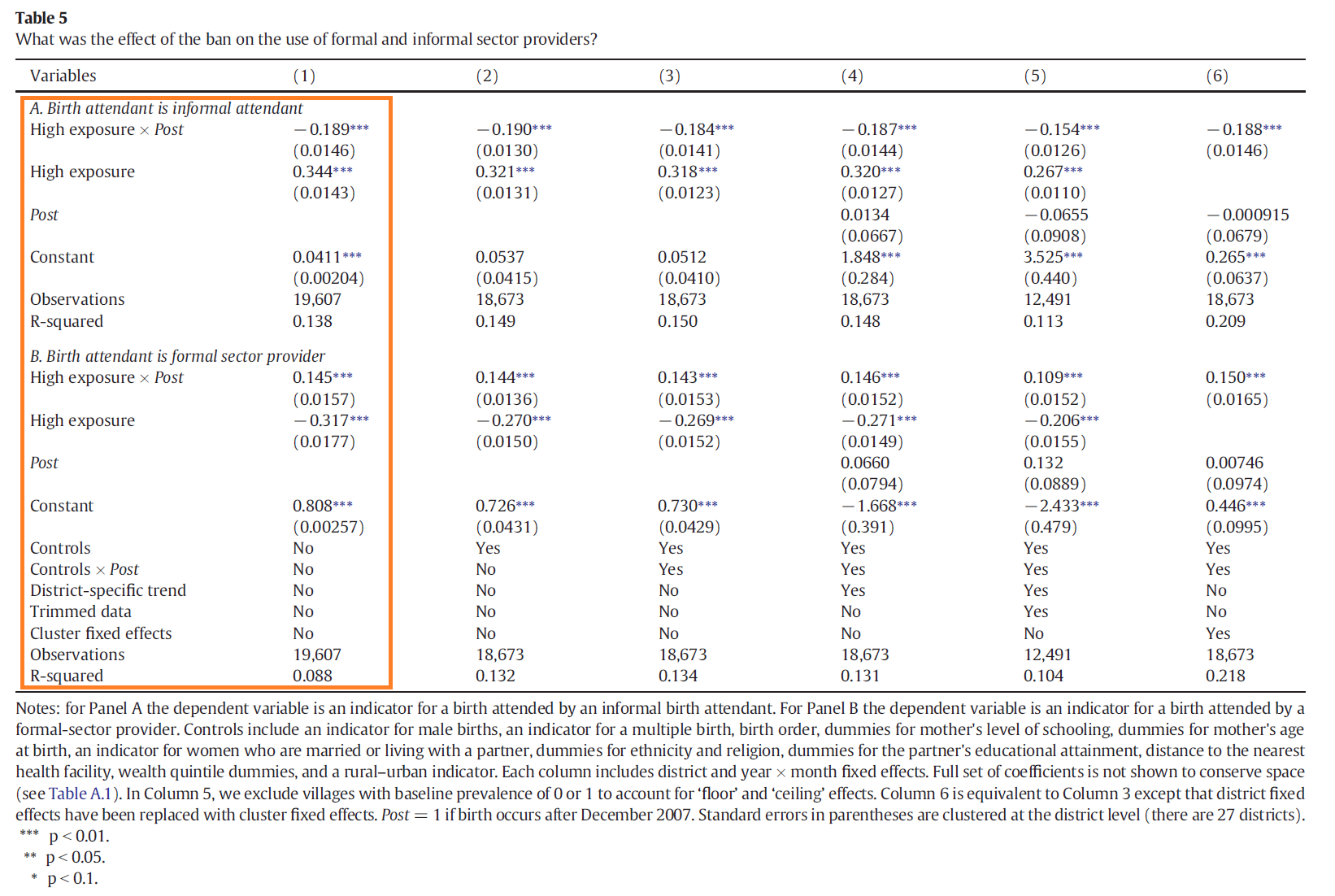

to those in Table 5, Panel A, Column 1 of the paper?

Question 9

You are using the same data as Professor Godlonton and Dr. Okeke, so you should be able to replicate their coefficient estimates and standard errors exactly. Have you done it?

Read the notes below Table 5. See if you can modify your regression command so that your results are precisely identical to those in the paper.

Hint 1: you will need to drop the observations with missing values of tba from the data frame.

Hint 2: to cluster your standard errors by district, you will need to set cov_type to cluster and cov_kwds to

{'groups': e4data['district']}. Both of these are arguments to fit().

Empirical Exercise

Start by generating a new script that loads E4-GodlontonOkeke-data.dta and uses your answers

to the in-class activity to generate the variables needed to replicate Column 1 of

Table 5. Then add the following code, which defines a program reshape_regs() that takes output from a regression and

reformats the results to look like a column of a regression table.

def reshape_regs(olsresults):

results = pd.DataFrame({'coef': olsresults.params,

'std_err': olsresults.bse,

'pval': olsresults.pvalues})

results = results.tail(2)

results['stars'] = results['pval'].apply(

lambda x: '***' if x <= 0.01 else ('**' if x <= 0.05 else ('*' if x <= 0.1 else ''))

)

results['coef'] = results['coef'].map(lambda x: f"{x:.3f}")

results['coef'] = results['coef'] + results['stars']

results['std_err'] = results['std_err'].map(lambda x: f"{x:.3f}")

results = results.astype(str)

results['std_err'] = results['std_err'].map(lambda x: f"({x})")

results = results[['coef', 'std_err']]

results.insert(0, 'var_num', range(len(results)))

results = results.reset_index()

results = (

results.melt(id_vars=['index', 'var_num'], var_name='type', value_name='est')

)

results = results.sort_values(by = ['var_num', 'type'])

results = results[['index', 'type', 'est']]

return results

Question 1: Replicating Column 1 from Tables 5 and 6

Part (a)

Estimate a difference-in-differences specification that replicates Table 5, Panel A, Column 1. Then use the program we defined above to clean up your results and store them in the data frame c1, as illustrtated in the code below:

T5AC1 = smf.ols('tba ~ highxpost + high_exp + C(district) + C(time)', data = e4data).fit(

cov_type='cluster',

cov_kwds={'groups': e4data['district']})

c1 = reshape_regs(T5AC1)

c1 = c1.rename(columns={'est': 'TBA'})

print(c1)

You can also use the code below to store the R-squared and the number of observations so

that they can be added to the results table later.

N1 = T5AC1.nobs

R2_1 = round(T5AC1.rsquared, 3).astype(str)

Part (b)

Now replicate Table 5, Panel B, Column 1 (the same specification with the sba dummy

as the outcome variable) and store your results.

Part (c)

Recode the m3h variable to generate a dummy for having a friend or relative

as the birth attendant. Use this variable to replicate Table 6, Panel A,

Column 1. Store your results.

Part (d)

Now generate a variable alone that is equal to one minus the maximum of

the tba, sba, and friend variables. Use this variable to replicate

Table 6, Panel B, Column 1. Store your results.

Hint: e4data[['x', 'y', 'z']].max(axis=1) will find the row-specific maximum of the variables x, y, and z.

Part (e)

Use merge() to combine the results from your four regression specifications. The code below

illustrates the first step, combining the results from the first two regressions into a single data frame.

results1 = c1.merge(c2, on=["index", "type"], how="left")

print(results1)

Once you have combined all four regression specifications into a single data frame,

drop the type column (which was helpful when merging the results from the different regressions),

modify the variable labels in the term column, and rename the term column so that it has no column name. You should also

use pd.concat() to add rows containing the number of observations in each specification and the R-squared. If you want,

you can also add rows indicating which fixed effects are included.

Once you have a nicely formatted data frame, export it to excel by modifying the code from Empirical Exercise 3.

Question 2: Assessing the Common Trends Assumption

Next, assess the validity of the common trends assumption by replicating

the first two columns of Table 2 (we don’t have the outcome data needed

to replicate Columns 3 and 4). Start by reading in the data as a new data frame, q2data. Use the option

convert_dates = False so that the time variable will read in as a number (indexing the month) rather than a date.

Part (a)

Drop the observations from after the ban was in place. Then, interact the time variable, which indexes the month of birth, with the high_exp variable. This should

give you all the variables needed to replicate the first two columns in Table 2.

Part (b)

Replicate columns 1 and 2 from Table 2 to the best of your ability. Store your results.

Part (c)

Export your results to excel as a nicely formatted table (all of the guidance from Question 1 still applies).

Additional Activities

If you are looking for ways to expand your program evaluation skills further, extend your answer to Question 1 by including district-specific time trends,

as Professor Godlonton and Dr. Okeke do in Columns 4 through 6 of Tables 5 and 6. Alternatively, you can replicate the main analysis

using a continuous measure of treatment intensity: the interaction between the level of TBA use prior to the ban and the post dummy. Generate

this new treatment variable using your existing meantba variable, and then estimate regressions that control for meantba and its interaction

with post. How do the results from these alternative specifications compare to those reported in the paper? Finally, consider using DHS cluster fixed effects

and month of birth fixed effects in the same specification. Do the DHS cluster fixed effects reduce the standard errors?

This exercise is part of the module Diff-in-Diff in Panel Data.